In the last segment of our commercial pricing guide we will tackle the least talked about and most misunderstood portion of your invoice; the licensing fees. I will go over what they are, why you should be using them, and my preferred method for calculating them no matter who my client is!

To date you've learned about why it is important to price your work, how to invoice your clients for costs associated with your production, how to find out what you are worth, and now today let us talk about your license fee.

What Is A License/Usage Rights

The license is an agreement between you the photographer and the client as to the usage rights that have been granted for a given project. It might help if you think of the license as a lease and the usage rights as the terms of that lease. When you create a commercial image, or any image for that matter, you as the creator are always the copyright holder. When you give your images to a commercial client, you are not selling your images to them, but rather, renting. Sure the client pays you for your time to create the vision and that is what your creative fee covers. However, because each client is so unique and has such varying demands for your images, we can’t possibly rely on your fixed rate creative fee to cover all these variable possibilities. Issuing your clients a license allows you to “rent” your images for their specific needs.

Why Is It Important?

Without a license, the client is completely free to interpret the usage rights however they wish and this can lead to some rather unpleasant situations. One famous example that shows the power of a license is that of the Nike logo. The creator of the Nike swoosh logo was originally paid just $35 for her creation. At the time Nike was in its infancy and the creator had no reason to believe the company would be worth anything, much less, stay in business. Since there was not a license in place the creator of the logo was not entitled to any royalties resulting from the massive growth of the company which resulted in her creation being one of the world’s most recognizable logos. Nike later rewarded the creator with shares of its company; however not all clients will be this giving. To protect yourself and your clients from possible disputes simply draft up a license that both parties can feel good about. The license is your ticket to a safe and prosperous long term business relationship.

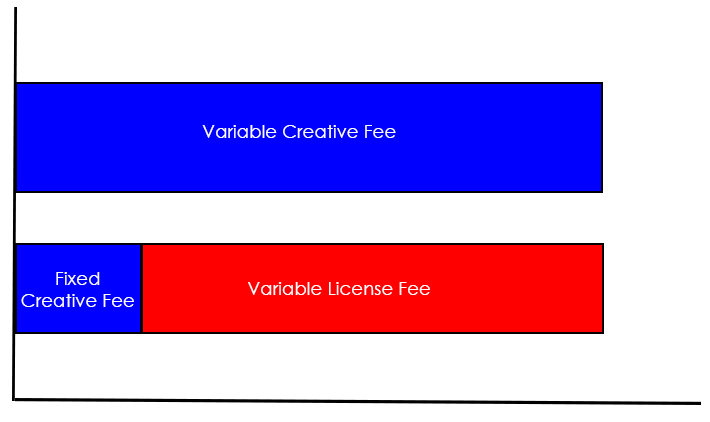

Your license will be a crucial part of your commercial invoice because it allows you to scale your invoices based on the type of projects you receive. It wouldn’t make sense to try and raise your creative fee to scale your invoices because the creative fee, as we discussed in the previous article, is based upon how much your time is worth. It is a fixed fee. Your time should not be worth more for certain clients as opposed to others. If you have a day rate of $2000, then that is the creative fee you will quote to small local retailers as well as to Fortune 500 companies.

As you can imagine though, a Fortune 500 company will have far more use for your images then a local retailer. The local retailer might use your images to generate $100,000 worth of revenue each year, whereas the Fortune 500 company might use it to generate tens of millions in revenue. If both companies needed a picture of a shoe, clearly one of them stands to profit quite a bit more using the exact same image. There has to be a way for us to scale our invoices.

This is where the license comes in. Through the license you will be able to define the terms of usage for each company, and cater the scale of the project to their individual needs. The local company might only need your images for a couple thousand flyers, some local newspapers, and one billboard. The Fortune 500 company on the other hand might need to place your image in a TV spot, hundreds of billboards, international magazines, and on packaging. Once you know where and how the images will be used these will become the terms of your license agreement. You will bill for them separately from your creative fee and production charges, thus being able to charge for the exact exposure the project will receive, as opposed to raising your creative fee from client to client in an attempt to see what your client is currently worth. That is a terrible practice because you are basing your entire estimate on price gouging. If instead you leave the creative fee as a fixed rate, and modify your license fee and usage rights to suit the client, you can come up with an estimate that has some method to it as opposed to being drawn up from thin air.

How To Define Usage Rights

The first thing you need to do is ask your client what the intended use of the images will be. Will these images be strictly for business to business presentations? Will they be used for local flyers? Maybe they will be used in a full page ad for a national magazine? Whatever the case may be, you need to sit down with the client, and ask them rather bluntly the full details of their intended usage. The next question you will have to ask will be, how long do they intend to use these images for? It may seem like an odd question but it is an important one none the less. Most licenses are drafted with a time limit because in reality clients do not need an image for life. It is rather normal for clients to overhaul their products every couple years to re-brand themselves and keep up an appearance of being fresh and up to date.

Some clients will be under the unfortunate impression that once an image is created for them, it is theirs to use for as long as they please. Since the license is really more like a rental agreement, by asking for lifelong usage, the client is in fact asking to be overcharged. It is quite counter-productive to offer your clients a lifelong license when the odds are they will need new pictures after a few years. To keep costs down for your clients, it is best to offer a standard license term, generally between 1-5 years based on the life cycle of your client’s product.

Once you know all the details, you are able to create a legal document known as the usage rights that will clearly state each and every media outlet as well as its related time frame and all other pertinent information relating to the project. I won’t go over how to actually write a license because there is quite a fantastic article for that on the ASMP website. They have a very detailed guide on how to structure your license and how to word it properly.

How To Price Your License

The easiest and simplest way I have found to price a commercial license is to simply find out what the total media buy for your particular project is. The total media buy is another way of saying, how much money is your client spending on the media outlets where your image will appear. Most clients will have a pretty solid understanding of their marketing campaigns for which you are creating the images and will be able to offer you precise figures.

Marketing campaigns come in all shapes and sizes. Small local retailers might only intend to use your image in a local paper for 1 year. This might cost them $3500. A larger international retailer on the other hand might use your image in a multitude of places, and their budget for that might be $350,000.

In order to fairly value our work we employ what is known as a sliding scale. A sliding scale simply means that the more money your client spends on their marketing campaigns, the bigger the discount they receive on their license. The reason for this is quite simple. If we had a flat 20% license rate for all our clients then the client who only spends $3500 on his marketing will owe us $700. That is still fairly reasonable. Yet if we try and charge that same 20% to the client spending $350,000 we need to price our license at a whopping $70,000! That wouldn’t fly in any market.

On the other hand if we charged a 1% license rate, then our client spending $350,000 would only need to pay us a license fee of $3500. That is quite reasonable. However if we keep that 1% for our smaller local client and apply the 1% to his $3500 marketing budget, we are left with a $35 license fee. That hardly seems worth our effort.

As you can clearly see, we need to employ a sliding scale which allows us to charge a higher license rate for smaller clients to offset their smaller marketing budgets, whereas larger clients who have bigger marketing budgets will receive a smaller license rate from us so that we don’t over price our services.

How you structure your sliding scale and the percentages you use are completely up to you. There really is no “industry standard”. There are acceptable ranges and you will learn those over time as you price out projects within your own individual markets. As an example, here is how you might lay out such a sliding scale:

How Would This Work For Our Client?

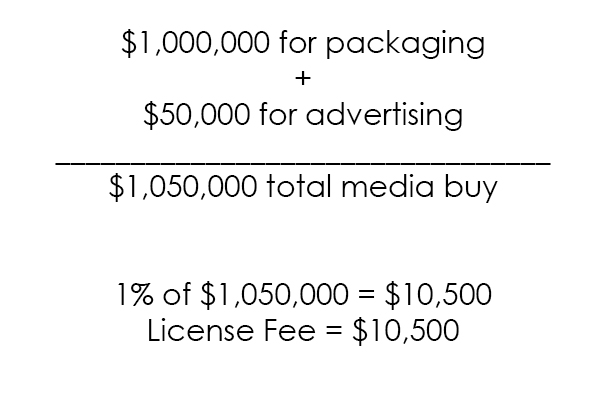

In Part 2 of this series we introduced our sample client. As you may recall, they needed two images of their useless systems, for which we have currently priced out the production charges and the creative fee. After speaking with the client they told us one of the two images we created would be used strictly for packaging of their product. They believe they will have a new version of the product after 2 years and anticipate creating no more than 100,000 units of the product. Their estimated packaging cost will be $1,000,000, or, $10 per package. The second image we created for them they wish to use to promote their product through a one page ad in a technical publication that has a quarterly release in the USA. They intend to advertise for four quarters and will be spending $50,000 to reach about 1 million people. These will be the only two media outlets so the clients total media buy in this case would be $1,050,000. If we reference our sliding scale from earlier in the article this particular client falls in the 1% licensing fee range. 1% of the clients $1,050,000 total media buy is $10,500 therefore that is our license fee for the project. It is as simple as that!

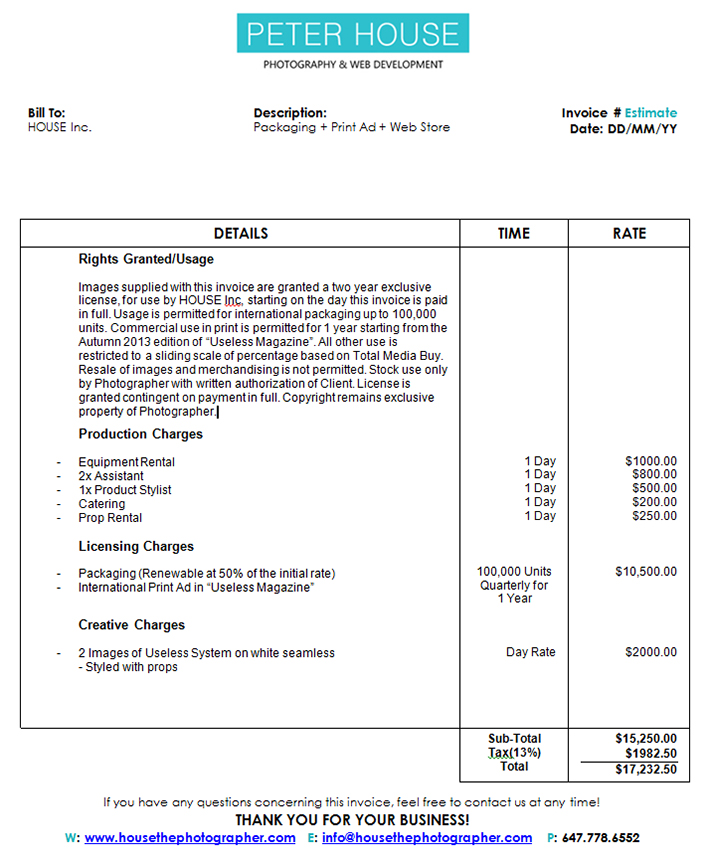

Adding It To The Invoice

Now that we have our license fee calculated we are ready to add it to our invoice. In addition to the license fee I will include a short and concise description of the usage terms right on the invoice. The full terms and conditions will be included with the invoice, but because nobody really likes to dig through all that legal jargon, I personally like to include the condensed overview on the invoice for easy reference. Finally, we get to add our license fee onto the invoice, and once we do that our entire commercial invoice is complete. This is what the completed invoice will look like:

Above And Beyond

As you may have noticed on the invoice, I have included a clause which states that upon renewal of the license, the fee will be applied at 50%. This is an option which you can include because once the terms of usage have been set in the license agreements, most clients don’t intend to go beyond them. Should a situation arise where they need to, you can offer them a price break for that unforeseen future use. An example of this might be if you shoot catalog images for a client. Styles usually change with every season and most images are not considered current beyond 2 years. If a client has unsold articles which he would like to place in a clearance sale, you can negotiate a license renewal, but it might not be fair to charge the full rate for such a use. Thus offering a 50% discount in these situations is a welcome courtesy.

This concludes our series on pricing your commercial projects. I hope you have found the articles useful and thorough. If you have any questions, feel free to include them in the comments section, or you can always email me directly. Till next time, feel free to visit us at Peter House – Commercial Photographer to follow our work.

If you'd like more professional tips on the business side of photography, Fstoppers produced a full course with Monte Isom, Making Real Money-The Business of Commercial Photography that includes lessons from the highest paid photography gigs out there along with free contracts, invoicing times, and other documents. If you purchase it now, you can save a 15% by using "ARTICLE" at checkout. Save even more with the purchase of any other tutorial in our store.

This is some exceptional information. Seriously...one of the best posts on Fstoppers.

Thanks for taking the time to share it, Peter

I hear many people advise using a percentage the media buy as a guide but have yet to talk to an actual photographer (I know 10 or 12 guys at various levels of the business)

who uses that model. I know an art buyer / producer and they are not all that forthcoming with those figures. I will ask her if photographers are given that info, or if very many ask for it in order to create a bid. I think much of the time they don;t know. or pretend they don;t know.

This series of articles has been enormously helpful, Peter. Thanks much for your commitment to providing your professional perspective to advance the industry. I know the first time I asked a commercial client for a licensing fee for web use they screamed bloody murder, but I ended up getting what I wanted for my photo. I appreciate your encouraging us to always think of licensing.

ha .. i get 25-35 cents on stock companys.. take that!!

Great article!

One quick question, your totaling both images into one licensing rate.

Wouldn't most separate the 2 image uses on different rates?

image one: 1m at the 1%= 10k

image two: 50k at the 15% rate = 7800

Is it standard to lump all images into the blocked fee.

Fantastic question.

According to our sliding scale above, if you were separating the license per picture, you would actually be charging 5% or 2% for the magazine submission. However, since the clients spending ($50,000) is in the upper limit of our 5% category, and since the client already has such a massive budget due to packaging, I would be tempted to move them into the 2% category for their magazine submission. Either way, the magazine submission would have a license rate of $1000 or $2500, depending on which category you lumped the client into.

Therefore if you separated your licensing by the image your total license fee would be $11,000, or $12,500. Not that much more then the bundled $10,500 we calculated in the article.

Ultimately it will be your call whether you want to itemize. On some projects where the images have very distinct uses, or if they have varying time frames, it might be easier to separate the licenses by image. It may make renewals easier. For most projects, I have personally found, that one bulk license fee per project does the job just fine and isn't all too different from the itemized license fee.

Thank you for the response. I'm used to the other side of the field where it's a agency or client dictating no licensing and only cost of day rate and want to break from the low pay freelance.

I've been looking for a good formula to price out usage, thank you.

Pricing/iicensing should be a negotiation; I wouldn't let a client dictate to me. Regarding usage fees, Fotoquote and Blinkbid are two applications that can help with this. Also check ASMP and APA, and the books "Best Business Practices for Photographers," and "Licensing Photography."

It seems like there should be a whole article on how to pitch licensing fees to uneducated clients. Especially if you've already worked with those clients without licensing fees before...

I think the word you're looking for is "Sticker Shock". And yes it is a bitch to deal with so some advice would be wonderful.

I was specifically referring to licensing fees which a lot of smaller clients are entirely unaware of and question the validity of. You're right that this adds to the sticker shock -- but more severely they might think we're ripping them off.

ASMP and APA have good resources to help with this--educating clients on fees and licensing. Also check out "Best Business Practices for Photographers" by John Harrington for these issues. Also, unfortunately some small clients will never get it, and/or won't/can't pay it even if they do.

How do you approach the situation if a client violates the licensing agreement?

Contact an attorney, and be glad that you made a licensing agreement with your client.

Great advice, I think one of the challenges of the industry today is there is an abundance of tutorials on how to make something, and not enough on how to charge for that work. So we're left with a marketplace of talented creatives that will work for free or cheap because they don't know their value.

Great article Peter, and incredibly timely as i was just mulling over licensing arrangements for a possible new client job that popped up today.

Brilliant :) Really usefuul stuff thanks :) Another article for another time perhaps is cresating contracts for these sorts of things.. Not just for writing a license but also for the contract you all sign before you start creating.

The entire series and specifically this article are incredible helpful. I am currently writing up an estimate and feel as though I have almost all the information I need to put together a professional document. There is only one question I have that I do not see covered, and that is if I have a client that it is only planning on using the photography for their website as background images, or images of product in use, and pack related shots as well. Thank you

You want to use my image in your local magazine? $100. It's a big magazine? $200. Send it to my paypal and we're good. Print a gazillion copies of it and make all the money you want from it.

I respect that view, but for photographers who have tens of thousands of dollars invested in gear, who pay their own business and health insurance, who are trying to make a living as a photographer without a side job or additional income source; we don't want clients to make a lot of money from our images without being cut in for our fair share.

FStoppers dropping that knowledge yet again! Dope stuff Mr. House.

I read this with interest as I have been asked to shoot images for a golf instructional book. It's all been very last minute and I own another business and so photography is about 40-50% of my time but working for that to be more. However, this was a great opportunity for me but I was clueless as to what to charge as an unknown freelance. I came up with a day rate but don't know what to ask for, for the usage, would the above still be applicable as a commercial job? I have made clear that the images are for this book only and I retain rights and they cannot be re-sold but for example they are asking if they re-issue the book in 4 years for example they don't want to pay again. Pretty sure I have WAY undercharged but any advice welcome!

Anyone know much about video content licensing? Definitely something i haven't been able to find too much info on. This will be blowing up soon

'you as the creator are always the copyright holder'

Do you still own the photograph if you are on a typical WFH (Work for hire) contract? Since my writing days, I understood work for hire as making you the same as staff with respect to copyright: anything you create on the client's time belongs to the client in a WFH. Is that true?

It is certainly that way for all tech contract jobs I have been in, and all creative jobs (writing, web design/development). Is photography different In this respect? It may be down to wording, but WFH contracts all typically say all work carried out under company time belongs to the company, and they have no specific deliverable (the client is simply paying for hours).

This should be spelled out in the contract, but my understanding is that no, you generally don't own the photograph's copyright if you shot it under a work for hire agreement.

Great series Peter. You did a great job explaining a lot of the "Why" along with the "What" and "How." Thanks so much! **For those who want continued reading, Bill Cramer with Wonderful Machine has a great article and seminar called Real World Pricing and Negotiating; Overview here: http://blog.wonderfulmachine.com/2013/02/real-world-pricing-negotiating/

As a side note; sometimes figuring out the correct fees for licensing can be downright tricky at times. There is software available (fotoQuote Pro 6 is the one I reference most often) that helps towards getting at least a general range to charge for most commercial work we might have to price out as photographers/videographers. I purchase it years ago and it has definitely made things easier when pricing out usage to clients.

Mark E.

www.nycphotostudio.com

Great Article! I have

a question on one of the items. The 13%

tax. Is this the sales tax that is charged

by the state/city you're doing business in. For example in Los Angeles

it's 9%, Thanks Peter!

Sales tax is unique to your area. He lives in Toronto and is charging the Ontario HST.

Great Article! I have

a question on one of the items. The 13%

tax. Is this the sales tax that is charged

by the state/city you're doing business in. For example in Los Angeles

it's 9%, Thanks Peter!

i´ve been trying to acept the license fee, but it hard fot me.

i think that a photographer should charge fot the cost of making an image, i think its not fare to charge more if the client is biger...

let say you go to a painter and hask him to make a paint for you bedroom wall, he doesnt hask ypu how big is the wall or how many people will go to you room...

if you nead 100dls to make an image thats the price the client shoul pay for it.

i know moat of you will not agree with me but that a point to discuss here.

:)

I understand where you are coming from but look at other creative businesses and you will find it is similar to the licensing in photography.

- A movie is not charged to the cinema companies at how much it cost to produce . The production company, actors etc will all get their royalties based on the box office figures.

- A recording artist (singer) does not get paid for what it costs to produce a song, they get paid for each time that song is used in a commercial/film or sold to a consumer.

And so the same works for the photographer. They get paid for each time the image is used. A way to imagine it could be that if it was a TV commercial then you could get paid each time it is aired. Or if it is on the side of a bus, each day the bus is on the road. However calculating license fees this way is difficult, instead using the sliding scale example here makes it a lot easier.

It is how I understand it and I hope it helps you too.

I still can't fathom how to charge a licensing fee to customers that want to use the images for social media or their website since this costs them no further outlay so it is difficult to put a percentage on.

Great article! Another question....what if someone just wants to use the photos for their website, social media, e-newsletter, etc. And/or, if they get written about a lot, they want to have art on file to give the publication to use if they write about them. They're not *paying* for their social media accounts, nor do they pay the publication to write a story on them, etc., so do licensing fees apply to these sorts of things? And if so, how do you tabulate?

I'm in the same position as you. I would like to know as well!

A brilliant set of articles Peter. Thank you very much. You certainly go into the friendly photography group, the ones willing to communicate and help rather than shield themselves away and provide nothing much to our industry.

I have a similar query to others here. How do you determine the license fee when the customer has no outlay for intended use of the images? (such as facebook, website etc). This is usually the case with a smaller client.

Thanks for any advice on this last issue. I think I'm the forth to ask the same thing here now but figured it was still worth asking to show it is a much anticipated answer!

I would like to know too!

This is a great article!!!! It's really hard to find something concise and easy to understand like this!

I've a question though, what happens for web marketing? How can you estimate the impact in revenues that your work will have? or does the client has to tell you how much income comes from their webpage? (or how much they invest in the webpage so you can estimate a porcentage?)

Thanks a lot for the info!!

Just came across your great article Peter. How do you price if the client won't share their total media buy?

Hi,

I would like to ask for advice regarding licensing issues, i have been hired to work for an assignment photography to shoot for interiors for client's portfolio, as i researched, it is to be categorized as commercial use, as the client would be posting it on their website to promote their work.

I have sent them the license agreement, and the client argued;

1.) Why should we pay you or signed the licensing agreement when we are the ones that funded the process we should own it.

2.) They also stated that technically i am under "work for hire", but i did not signed any contract.

3.) It is also being mentioned that, unless the entire exercise is being funded by me, owned by me, being paid by me then only i am the sole owner of everything. If i am not, i am still "working" under an entity whom have funded the entire operation.

So all in all, they argued that they should be owning the photos i took of their interior work and they could use it within their means.

I would really appreciate if anyone could let me know if i am wrong to asked the company to sign for the license agreement. And if is funded by them, am i not the owner of the photo. Are the photos not my own intellectual property?

And also, for the license agreement, can it be exercise outside US and UK? As the situation i stated above occurred in my country.

Thank you.

Peter that was very helpful but I would like to ask two things. Would licensing fees be similar in the UK? Also I am hoping to enter into an agreement with a company that obtains images to frame them and sell them to companies and retail outlets. How would I calculate the 'media buy' from which to derive the relevant percentage? Thanks, Julian

I'm having a bit of trouble licensing my editorial work. I'm coving for a trusted photographer who is out of town and recommended me to a high end lifestyle magazine. The problem is that the magazine is under the impression that because they are paying me for my time they receive all images with the copyright... This is not how I conduct my business and for roughly $50 an hour I'm not exactly willing to give up my copyright.

Any and all advice would be great.

Cheers

Great article.This was very helpful. A friend of mine has a small lifestyle clothing company and indy record label. He has requested 10 of my images to represent the company and help them celebrate their 25 year anniversary. How much should I charge to license out my images? Should I charge a flat fee for all 10 images or do charge per image? I'm leaning more towards a flat fee for all 10 but have no clue on how much to charge? I suppose I should ask what the media buy is. Could you please help?

Peter, these articles are great. .however how do you enforce the license? what happens when the client uses the images for other commercial uses outside of the license?

THANK YOU!! Very helpful jumping off point for me.

Great articles! Super helpful!.

.

Does the sliding scale which you use to determine licensing fees ever cap out? I'm currently in the process of bidding on a job and they won't tell me the total media buy. I'm sure it's a lot and I want to get compensated fairly but at the same time I want to win the bid. Any thoughts?

lol...damn good article, and just had found it ;)...

in any case...how can you verify the media-budget? I had an issue with Sony, regarding a boyband, and my problem was i could not verify, the were giving me decreased numbers....

Great info! Just curious how you would factor in social media, websites, etc. We all know for small business that is people's number one concern now. Also, what about the startups that ask for photos but have no clue about where they will be used for future ads.

Even if it an old article ... very helpful for us photographers. I am sure it is eye opening for a lot of photographers. Thanks a lot. Would love to have some advice how to actually write a picture licence ... the link within the article is not working anymore. :-)

What if a company is just asking to license and few photos from a previous photoshoot. Do you still add the creative fee? Even if they didn't hire you to take the photos and they wanted them after.